விஞ்ஞானக் கலை, இலக்கியத்தின் பிதாமகன்: மைக்கல்

கிரைக்டென் ( 1942 - 2008 )!

அண்மையில் , நவம்பர் 4, 2008, லாஸ் ஏஞ்சலிஸில் எழுத்தாளர் மைக்கல் கிரைக்டென்

புற்று நோயினால் மறைந்தபொழுது கலை, இலக்கிய உலகு அதிர்ச்சியடைந்தது. அந்த

அளவுக்கு இவர் தனது நோய் பற்றிய விபரங்களை அந்தரங்கமாக வைத்திருந்தார். இவரது

இறுதிக் கிரியைகளும் அவரது விருப்பத்தின் படியே அந்தரங்கமாகவே நடைபெற்றன.

ஆங்கிலக் கலை, இலக்கிய உலகிலுள்ளவர்களுக்கு மைக்கல் கிரைக்டன் ( Michael

Crichton ) நன்கு அறிமுகமானவர். இவர் எழுதிய

நாவல்களெல்லாம் வாசகர்கள் மத்தியில் மிகுந்த வரவேற்பைப பெற்றவை. நாவல்கள்

மட்டுமன்றி இவர் ஆங்கிலத் திரையுலகிலும் கொடி கட்டிப் பறந்தவர். தயாரிப்பாளராக,

இயக்குநராக, திரைக்கதை வசனகர்த்தாவாக, மூலக்கதை ஆசிரியராகவெனப் பல்வேறு

அவதாரங்களிவர் எடுத்தபோதும் அனைத்திலுமே வெற்றிக்கொடி நாட்டியவர். இவரது பல

நாவல்கள் திரைப்படங்களாக வெளிவந்து

உலகரீதியில் வ்சூலில் பெரும்சாதனையைப் படைத்துள்ளன. அண்மையில் , நவம்பர் 4, 2008, லாஸ் ஏஞ்சலிஸில் எழுத்தாளர் மைக்கல் கிரைக்டென்

புற்று நோயினால் மறைந்தபொழுது கலை, இலக்கிய உலகு அதிர்ச்சியடைந்தது. அந்த

அளவுக்கு இவர் தனது நோய் பற்றிய விபரங்களை அந்தரங்கமாக வைத்திருந்தார். இவரது

இறுதிக் கிரியைகளும் அவரது விருப்பத்தின் படியே அந்தரங்கமாகவே நடைபெற்றன.

ஆங்கிலக் கலை, இலக்கிய உலகிலுள்ளவர்களுக்கு மைக்கல் கிரைக்டன் ( Michael

Crichton ) நன்கு அறிமுகமானவர். இவர் எழுதிய

நாவல்களெல்லாம் வாசகர்கள் மத்தியில் மிகுந்த வரவேற்பைப பெற்றவை. நாவல்கள்

மட்டுமன்றி இவர் ஆங்கிலத் திரையுலகிலும் கொடி கட்டிப் பறந்தவர். தயாரிப்பாளராக,

இயக்குநராக, திரைக்கதை வசனகர்த்தாவாக, மூலக்கதை ஆசிரியராகவெனப் பல்வேறு

அவதாரங்களிவர் எடுத்தபோதும் அனைத்திலுமே வெற்றிக்கொடி நாட்டியவர். இவரது பல

நாவல்கள் திரைப்படங்களாக வெளிவந்து

உலகரீதியில் வ்சூலில் பெரும்சாதனையைப் படைத்துள்ளன.

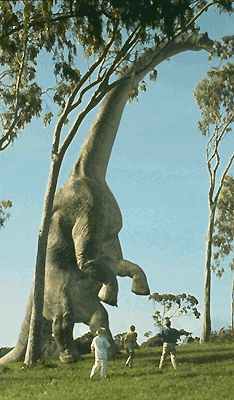

பிரபல

ஹாலிவூட் இயக்குநர் ஸ்டீபன் ஸ்பில்பேர்க்கின் இயக்கத்தில் வெளிவந்த இவரது

நாவலொன்று உலகரீதியில் 350 மில்லியன்

அமெரிக்கன் டாலர்களுக்கும் அதிகமாக வசூலில் சாதனை புரிந்துள்ளது. அந்தத்

திரைப்படம்தான் ஜுராசிக்பார்க். பல மில்லியன் வருடங்களுக்கு முன்னர்

இப்புவியுலகிலிருந்து அழிந்துபோன டைனசோர்களை மீண்டும் புதைபொருளாய்வில்

கண்டெடுக்கப்பட்ட அவற்றின் 'டி.என்.ஏ' (D.N.A) க்களிலிருந்து உருவாக்கி உலாவ

விடும்போது ஏற்படும் எதிர்பாராத விளைவுகளைப் பற்றிக் கூறும் அற்புதமான,

அறிவுக்கு விருந்தளிக்கும் திரைப்படம். நாவலும் கூடத்தான். திரைப்படம்

நாவலிலிருந்து சிறிது மாறுபட்டிருந்தாலும்,

ஜுராசிக் பார்க் திரைப்படத்திற்கான கதாசிரியர்களில் இவரும் ஒருவர். ஜுராசிக்

பார்க் நாவலின் கதை மட்டுமல்ல வரும் பாத்திரங்கள்

அனைவருமே மறக்க முடியாத வகையில் நன்கு உருவாக்கப் பட்டிருந்தார்கள், குறிப்பாகக்

கணிதவியல் அறிஞராக வரும் 'ஜெவ் கோல்ட்பிளம் (Jeff Goldblum)'.இவரது 'கயாஸ்

தத்துவம் ( Chaos Theoiry) மேற்படி டைனசோர்களை உருவாக்குவதிலுள்ள அபாயங்களை

எச்சரிக்கை செய்யும். அதன்படியே திரைப்படத்திலும் டைனசோர்களின் எதிர்பாராத

நடவடிக்கைகள் அமைந்திருக்கும். விஞ்ஞானத்தின் நன்மை, தீமைகளை, எதிர்பாராத

விளைவுகளை நாவலும், திரைப்படமும் நன்கு படம் பிடித்துக் காட்டும். இவரது பல

படைப்புகள் பல்வேறு பல்கலைக்கழகங்களில், கல்லூரிகளெல்லாம் பாடத்திட்டங்களில்

பயிற்றுவிக்கப்பட்டு வருகின்றன. இவரைப் பற்றி நான் கவனிக்க ஆரம்பித்ததே இவ்விதமான

சந்தர்ப்பமொன்றில்தான். கனடாவிலுள்ள கல்லூரியொன்றில் 'விஞ்ஞானப் புனைவு' (Science

Fiction)

என்றொரு பாடத்திற்காகப் படிக்க வேண்டிய மூன்று நாவல்களில் இவரது ஜுராசிக்

பார்க்கும் ஒன்று. பார்க்க வேண்டிய திரைபப்டங்களில் ஜுராசிக் பார்க்கும் ஒன்று.

அப்பொழுதுதான் முதன்முறையாக இவர் எனக்கு அறிமுகமானார்.

மருத்துவரான இவரது நாவல்களெல்லாமே உயிரியல விஞ்ஞானிகளுக்குச் சவால் விடும்

வகையில் அமைந்திருந்தன. இவரது இன்னுமொரு நாவலான 'அன்ரொமீடா ஸ்ட்ரெயி'னும் (THE

ANDROMEDA STRAIN ) திரைப்படமாக வெளிவந்து புகழ்பெற்றது

குறிப்பிடத்தக்கது. 'டேர்மினல் மான்' (THE TERMINAL MAN), 'ஜுராசிக் பார்க் II',

'கொங்கோ (CONGO)' போன்ற இவரது பல நாவலகள்

திரைப்படங்களாக வெளிவந்துள்ளன. 'த கிரேட் ட்ரெயின் ரொபெரி (THE GREAT TRAIN

ROBBERY), ஜூல் பிரைனரின் நடிப்பில் வெளிவந்த

'வெஸ்ட் வேர்ல்ட் ( WESTWORLD)' போன்ற பல புகழ்பெற்ற ஆங்கிலத் திரைப்படங்களின்

இயகுநராகவும், கதாசிரியராக்வும்

இருந்திருக்கிறார்.

இவரைப் பற்றிய மேலதிக விபரங்களைப் பதிவுகள் வாசகர்களுக்காக அவரைப் பற்றிய

இணையத்தளத்திலிருந்து மீள்பிரசுரம்

செய்கின்றோம். - வ.ந.கி -

Michael Crichton!

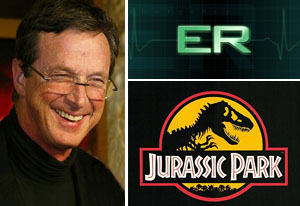

Michael

Crichton, who died in Los Angeles on November 4, 2008, was a writer and

filmmaker, best known as the author of Jurassic Park and the creator of ER.

His most recent novel, Next, about genetics and law, was published in December

2006. Crichton graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College, received his MD

from Harvard Medical School, and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Salk

Institute for Biological Studies, researching public policy with Jacob

Bronowski. He taught courses in anthropology at Cambridge University and

writing at MIT. Crichton's 2004 bestseller, State of Fear, acknowledged the

world was growing warmer, but challenged extreme anthropogenic warming

scenarios. He predicted future warming at 0.8 degrees C. (His conclusions have

been widely misstated.) Michael

Crichton, who died in Los Angeles on November 4, 2008, was a writer and

filmmaker, best known as the author of Jurassic Park and the creator of ER.

His most recent novel, Next, about genetics and law, was published in December

2006. Crichton graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College, received his MD

from Harvard Medical School, and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Salk

Institute for Biological Studies, researching public policy with Jacob

Bronowski. He taught courses in anthropology at Cambridge University and

writing at MIT. Crichton's 2004 bestseller, State of Fear, acknowledged the

world was growing warmer, but challenged extreme anthropogenic warming

scenarios. He predicted future warming at 0.8 degrees C. (His conclusions have

been widely misstated.)

Crichton's interest in computer modeling went back forty years. His

multiple-discriminant analysis of Egyptian crania, carried out on an IBM 7090

computer at Harvard, was published in the Papers of the Peabody Museum in

1966. His technical publications included a study of host factors in pituitary

chromophobe adenoma, in Metabolism, and an essay on medical obfuscation in the

New England Journal of Medicine.

Crichton's first bestseller, The Andromeda Strain, was published while he was

still a medical student. He later worked full time on film and writing. One of

the most popular writers in the world, his books have been translated into

thirty-six languages, and thirteen have been made into films.

He had a lifelong interest in computers. His feature film Westworld was the

first to employ computer-generated special effects back in 1973. Crichton's

pioneering use of computer programs for film production earned him a Technical

Achievement Academy Award in 1995.

Crichton won an Emmy, a Peabody, and a Writer's Guild of America Award for ER.

In 2002, a newly discovered ankylosaur was named for him:

Crichtonsaurus bohlini. He had a daughter, Taylor, and lived in Los Angeles.

Crichton remarried in 2005.

CRICHTON, (John) Michael. American. Born in Chicago, Illinois, October 23,

1942. Died in Los Angeles, November 4, 2008. Educated at Harvard

University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, A.B. (summa cum laude) 1964 (Phi Beta

Kappa). Henry Russell Shaw Travelling Fellow, 1964-65. Visiting

Lecturer in Anthropology at Cambridge University, England, 1965. Graduated

Harvard Medical School, M.D. 1969; post-doctoral fellow at the Salk

Institute for Biological Sciences, La Jolla, California 1969-1970. Visiting

Writer, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1988.

Awards: Recipient of Mystery Writers of America's Edgar Allan Poe Award, 1968

("A Case of Need", written under pseudonym Jeffery Hudson);

and 1980 ("The Great Train Robbery"). Association of American Medical Writers

Award, 1970 ("Five Patients"); Academy of Motion Picture Arts

and Sciences Technical Achievement Award, 1995 ("for pioneering computerized

motion picture budgeting and scheduling"); George Foster

Peabody Award (for "ER"); Writer's Guild of America Award, Best Long Form

Television Script of 1995 (for "ER") Emmy, Best Dramatic Series,

1996 (for "ER"). Ankylosaur named Crichtonsaurus bohlini, 2002.

Associations: Member of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Author's

Guild, Writers Guild of America, Directors Guild of America,

P.E.N. America Center, Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, Phi Beta

Kappa. Board of Directors, International Design Conference at Aspen,

1985-91; Board of Trustees, Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, La Jolla,

1986-91. Board of Overseers, Harvard University, 1990-96. Board

of Directors, Drug Strategies, 1994-, Author's Guild Council, 1995-, Board of

Directors, Gorilla Foundation, 2002-, Board of Trustees, Los

Angeles County Museum of Art, 2006-

References: Contemporary Authors, 1971-; Who's Who in America, 1974-; Current

Biography, April 1976; Film Encyclopedia, 1979-; International

Motion Picture Almanac, 1996; International Television & Video Almanac, 1996.

Novels

THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, Knopf, 19699

THE TERMINAL MAN, Knopf, 1972

THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY, Knopf, 1975

EATERS OF THE DEAD, Knopf, 1976

CONGO, Knopf, 1980

SPHERE, Knopf, 1987

JURASSIC PARK, Knopf, 1990

RISING SUN, Knopf, 1992

DISCLOSURE, Knopf, 1994

THE LOST WORLD, Knopf, 1995

AIRFRAME, Knopf, 1996

TIMELINE, Knopf, 1999

PREY, Harper Collins, 2002

STATE OF FEAR, Harper Collins, 2004

NEXT, Harper Collins, 2006

Non-Fiction

FIVE PATIENTS: The Hospital Explained, Knopf, 19700

JASPER JOHNS, Abrams, 1977

ELECTRONIC LIFE, Knopf, 1983

TRAVELS, Knopf, 1988

JASPER JOHNS (revised edition), Abrams, 1994

Published Screenplays

WESTWORLD, Bantam Books, 19755

TWISTER (with Anne-Marie Martin), Ballantine Books, 1996

Films

PURSUIT, ABC Movie of the Week, 1972. (Director))

WESTWORLD, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1973. (Writer/Director)

COMA, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1978. (Writer/Director)

THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY, United Artists, 1979. (Writer/Director)

LOOKER, The Ladd Company, 1981. (Writer/Director)

RUNAWAY, Tri-Star Pictures, 1984. (Writer/Director)

PHYSICAL EVIDENCE, Columbia Pictures, 1989. (Director)

JURASSIC PARK, Universal, 1993 (Co-writer)

RISING SUN, Twentieth Century Fox, 1993 (Co-writer)

DISCLOSURE, Warner Brothers, 1994 (Co-producer)

TWISTER, Warner Brothers/Universal, 1996 (Co-writer, Co-producer)

SPHERE, Warner Brothers, 1998 (Co-producer)

13TH WARRIOR, Touchstone, 1999 (Co-producer)

Other Films From Crichton's Books

THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, Universal, 19711

THE CAREY TREATMENT, MGM, 1972

DEALING: OR THE BERKLEY TO BOST0N FORTY-BRICK LOST BAG BLUES, Warner Bros,

1972

THE TERMINAL MAN, Warner Bros, 1974

CONGO, Paramount, 1995

LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK II, Universal, 1997

TIMELINE, Paramount, 2003

Television

ER, NBC, 1994 Creator, (co-exec. producer)

Computer Games

AMAZON, Tellarium, 19822

TIMELINE, Eidos, 2000

*** *** ***

FOR YOUNGER READERS

Q & A with Michael Crichton

Where were you born? What's your background?

I was born in Chicago in 1942,

during World War II. Not long after my birth my father was drafted. When he

went overseas I lived with my mother and sister in Fort Morgan, Colorado, a

town of about 2,000 people, until the war was over. Then we moved to Roslyn,

Long Island which is where I grew up and went to school. Where were you born? What's your background?

I was born in Chicago in 1942,

during World War II. Not long after my birth my father was drafted. When he

went overseas I lived with my mother and sister in Fort Morgan, Colorado, a

town of about 2,000 people, until the war was over. Then we moved to Roslyn,

Long Island which is where I grew up and went to school.

What got you to start writing? My dad was a journalist, so I saw him typing

when I was growing up, so it seem like a normal occupation, to sit down and

type something as your job. I myself began writing pretty young. In the third

grade we all had to do puppet shows and most of the kids just did a little

skit. I wrote a 9 page play that my father had to type up for me, using carbon

paper, so all the kids would know their parts. And I wrote a lot in fifth and

sixth grade, too, and I became known for it; I was the weird kid who wrote

extra assignments the teacher didn't ask for. I just did it because I liked

writing so much. I was tall and gangly and awkward and I needed to escape, I

guess.

When I was fourteen, my family took a car trip to the West, and we visited

Sunset Crater National Monument in Arizona. I thought it was very interesting

and people should know about it. My parents suggested that I write an article

about it for the New York Times travel section, which accepted articles by

regular people who had had an interesting travel experience. So I wrote my

article and sent it in, and the New York Times printed it, which really

encouraged me. (They paid $60. I still have the check stub.) I also wrote for

the town newspaper, covering high school sports, and for the school paper.

Later, I wrote for the college newspaper, the Harvard Crimson.

I wanted to become a writer but didn't think it was likely I could make a

living at it, so I went to medical school. I was looking forward to becoming a

doctor. Then I started writing paperback thrillers to pay my way through

medical school, and the books began to be successful. Finally I just decided

to do it full time, after graduation.

Where do you get your ideas for your books? I wish I knew. They just seem to

come from nowhere. But often I think people put too much emphasis on the

"idea" behind a story, anyway. First of all, there isn't just one idea in a

story, there are lots of ideas. And second, an idea by itself isn't worth much

until you do the work necessary to get it down on paper. And in the course of

doing the writing, the idea often changes. It's similar to the difference

between having an idea for a building, and actually constructing the building.

The building often turns out differently from the original plan or intention.

How did you become such a good writer? Plenty of writing! I began writing

really diligently when I was in high school, and I kept at it.

What advice do you have for someone who wants to be a writer? I am sorry to

say I don't have any advice except to write as much as you can, and keep

writing. It's often said that if you can do anything else with your life, you

should, because the life of a writer can be a difficult one. I think that's

good advice.

If you really want to pursue writing, there are some journals you can use for

guidance and reference: The Writer, and Writer's Digest, both of

which have articles about writing, and list publishers for books and

magazines. Nearly all libraries have these journals.

Do you read your books once they are published? No. It takes a long time to

write a book, and by the time it is finally on the store shelves I

am usually working on a new one. From time to time, I've gone back and looked

at earlier books (it's not really fair to say I read them, I just

sort of flipped through the pages and read a paragraph here and there.) I

usually like them, although they usually seem to me to have been

written by somebody else.

Why do you like to write science-fiction books? I don't know, I have a

technical background and technical stories interest me. So that's what

usually comes out of my head. But I have also written historical novels and

non-fiction.

I try not to make too many judgements about the books that come out of me. I

just write them and carry on. I try not to define myself, or

what I do, because any definition is limiting. I like to leave the future

open.

What makes you write your stories the way you do? I have no idea. It's just

how they come out of me. Sometimes people ask, "Why did you write this scene,

or this character?" I don't have a good answer to questions like this. It's

like getting dressed in the morning. If somebody asked you why you put on the

clothes you did, you'd make up an answer, but the truth is you probably just

got up and put on something you thought looked good for that day. And when I

decide a scene, or a character, it's sort of the same. I just write something

I think works well.

What types of books do I like to read? When I was a teenager, I read lots of

science fiction. Now, I tend to read non-fiction almost exclusively. I hardly

ever read fiction.

Do you base the characters on people you know? Not usually. Once or twice,

I've wanted to pay somebody back so I put them in a book in an unflattering

way. But they're usually disguised so that even the person wouldn't know.

Sometimes I base characters on people I know about, but haven't met. In

Jurassic Park, many people have noticed that the character of Alan Grant was

quite similar to a real dinosaur paleontologist named Jack Horner. But I never

met Jack until years later, after the movie came out.

Most often I take bits and pieces of real people and combine them into a

character that does not correspond to any single person.

How long does it take to write a book? It's difficult for me to say. Usually,

an idea "cooks" in my head for a very long time before I begin to write it.

During that preparation time I will make notes and do research. The actual

writing can be relatively quick---four to fifteen months---but I could the

preparation as part of the work. So in that way, The Great Train Robbery was 3

years. Jurassic Park was 8 years. Disclosure was 5 years. Sphere is an odd

example: I started it and wrote part of it, but didn't have a good ending, so

I stopped. Twenty years later, I picked

it up again and finished it in about two months. So: did it take 20 years, or

two months?

Who most influenced your career? Arthur Conan Doyle, Mark Twain, and Alfred

Hitchcock.

What are your working methods? I get up early, usually at 6 AM, and drive 2

miles to my office, where I begin work in isolation---and much of the year, in

darkness. I like my surroundings to be quiet, and I work most easily alone. My

assistant comes in later, around 9:30. I continue working until lunch-time.

After lunch, I answer mail, or fuss with what I have written. I quit about 3

PM, take some exercise, and go home.

Usually I begin writing each morning by rereading what I wrote the day before,

and revising it. I try not to get bogged down in the rewrites, but to move on

to the new work each day. I prefer to revise in passes---do it once, then go

back another time, do it again. I don't try to make it perfect because I know

I am going to come back to it.

As the novel progresses, I work longer and longer hours. Pretty soon I work

during the afternoon right up to dinner. Eventually I come back after dinner

to work some more in the evening. I usually can finish a draft in a few

months.

I experience a lot of doubts when I am working; I never feel confident. About

two hundred pages in, I decide the book's no good, and it was a mistake ever

to begin it. And I think there is no way to fix it, and I am generally

miserable…If I tell my friends about these concerns, they just say, "Oh, I'm

sure you'll work it out." This is very irritating.

How do you pronounce your last name? It sounds like Cry-ten (rhymes with

frighten). It's Scottish.

What type of schooling have you had? I went to public schools in New York;

Greenvale Elementary and East Hills Elementary. I went to Roslyn High School.

I have a B.A. in Anthropology from Harvard College and a M.D. from Harvard

Medical School. I haven't gone back to school since then.

What were you like growing up? I am the oldest of four children. My father was

a journalist and my mother was a homemaker. I grew up in Roslyn, New York,

which is a suburb of New York city, on Long Island. Most of my time growing up

was painful. I was shy and awkward; at the age of 13 I was 6'7" tall, and I

weighed 125 pounds. They made me wear heavy shoes so I wouldn't blow over in

the wind. My brothers and sisters were much more gregarious than I was. I was

pretty quiet and studious. I played basketball; I was also on the track team.

I was my class vice president in my senior year.

I also wrote for the high school paper, and the local town paper, where I

covered high school sports (I was also the photographer.) I began writing in

this practical journalistic way, and I continued to write in college, for the

school paper, the Harvard Crimson. I was very lucky in high school to have

teachers who encouraged my writing.

What was you mother like, and did she help you in your life? My mother was a

very dedicated parent and very encouraging to her children; she used to drive

me to the next town, Great Neck, because it had a better library, so I could

do my school research there. She was very interested in all kinds of art, and

would drag her kids to museums and plays at least once a week. We all

complained bitterly---not another museum!---but the result was that I'd been

exposed to a lot by the time I got out of high school. I felt I had a lot of

support for my work and writing in my family, growing up, even though

emotionally it was a pretty crazy house with lots of turmoil and yelling and

screaming.

Why did you decide not to become a doctor? There were really two reasons. The

first was that my writing in medical school had become successful and I

realized I could probably support myself as a writer. The second reason was

that medicine really wasn't for me. I didn't like being on call; I didn't like

getting called at night. I just wasn't suited for a physician's life.

Where did you get your interest in computers, and did you like them as a kid?

There weren't any computers when I was a kid. But I've had an interest for a

long time; I did my college thesis in the 1960s on a computer, which was a

huge IBM mainframe. It took a whole building at Harvard and I think it was a

12K machine. About as powerful as a Gameboy now! I got interested in personal

computers in the late 70s and started writing on computers back then. So my

interest just developed as time went on...

No computers? What else didn't you have as a kid? Before the age of ten, no

TV, no direct dial phones, no jetliners, no credit cards…a lot of stuff didn't

exist in my childhood. A great deal has happened during my lifetime!

When you write, do you think of a movie? It's impossible not to think of it

from time to time, but in general I try not to, for several reasons. First,

it's possible no movie will be made. Second, the director will decide what

parts of the novel will go into the movie, and he may very well cut your

favorite parts and add others. So you might as well just write the scenes or

characters you want in the book. And third, to worry about practical

considerations when you write a chapter (how can they ever film this?) is a

waste of time. The experience of movies is that

certain apparently simple scenes prove impossible to shoot, and certain

extremely difficult scenes turn out to be not so bad, after all.

So in the end, I try to just write a book and not to think about what may

happen to it after publication-not only in terms of a movie, but also in terms

of what readers will think, what reviewers will say, and so on. Because all

that is beyond my control. It happens after the book is published. All I can

do is write a book, so I just focus on that.

Courtesy:

http://www.michaelcrichton.net/aboutmichaelcrichton-biography.html |